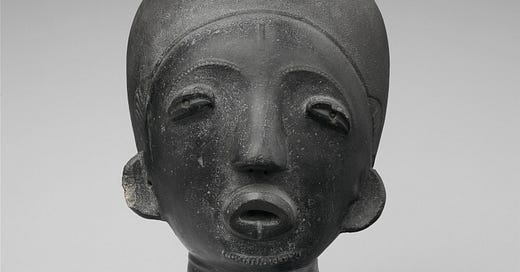

What does the phantom body

of the disembodied head

remember?

It remembers the gunmetal skin

I effaced in fleece. Consider me not,

continent. Let me pass unscathed.

You will see my hands at all times.

The head, in diaspora from its body,

is in another country.

I harbor an exaggerated startle in my flesh—

a scampering of impalas

within the choreography of felled

follicles rising again,

as traumatic amputation

dismembers me, once more,

from remembering.

Lindsay Graham prays for the natural disaster

that will help him call on the power he believes in,

something like god,

with a large capacity to assault enemies.

Gunscopes, consider us not. The hollow-tip dome

has never been far from our heads, anyway.

Due to scheduling conflicts:

beleaguered under the weight

of coalescing laser sights preempting blood,

the machine hum of tinnitus

and the industrial revolutions of the bony gears in my ears;

and cowering

under the vertigo of pestilence:

although I have heard the petitions of my body,

I have been unable to have this breakdown

until now.¶

© Tolu Oloruntoba

Note:

Today’s NaPoWriMo prompt was ekphrastic in nature, requiring the study of a piece of art from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Regarding the topic, I was struck by this quote from an interview with trauma therapist Janina Fisher: “For some reason, the amygdala on the right hemisphere side seems to be the center for traumatic memories. What this meant was that we couldn’t work with the narrative memory of the event because post-traumatic memories are held as non-verbal feeling and physical reaction memories—what I call body memories.” The title of the poem is from that interview.

Note on image:

Memorial Head (Ntiri) 17th century (?) | Akan peoples | On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 352 | Image in public domain